Creatine: what is it? what is it for?

In the vast universe of sports supplements, creatine monohydrate stands out for its popularity and is considered a very valid ally in sports supplementation. But what exactly is creatine? We will talk about it in this article. We will discover why it is a totally safe food supplement and why it can be a valid support in our gym training regime and endurance activities.

We’ll discuss timing, i.e. when to take creatine, and whether it’s best before or after training. Finally, we will understand why we need to wait to evaluate the effects of creatine after a month of use. This article presents a comprehensive overview of creatine, helping the reader understand if and how this supplement may be suitable for their lifestyle and exercise routine.

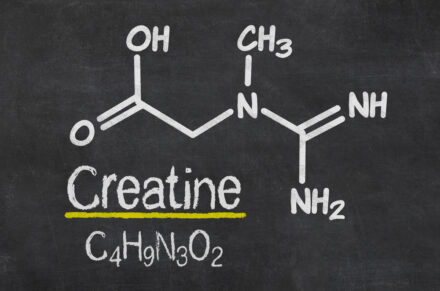

What is Creatine?

This molecule was discovered in 1832 by the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, who was the first to extract it from meat and for this reason called it creatine (from the Greek “kreas”, meat). Creatine is an organic compound naturally present in our body. It is a non-protein amino acid derivative, meaning it is not used to build proteins. Creatine is in fact a metabolite involved in various metabolic and biochemical reactions in our body.

It is found naturally in our cells and therefore also in our muscles and is constantly produced by our body. The main food sources of creatine are in fact purely those of animal origin. Creatine is found mainly in meat, poultry and fish, which contain on average 4-5 g of creatine per kg.

In the article “best foods for muscle mass” we recommend some foods, such as meat, precisely because of their high creatine content.

In addition to dietary intake, creatine is also synthesized by our body in the liver and kidneys, producing approximately 1 g per day of this nutrient starting from the amino acids arginine, methionine and glycine. Whether it comes from food sources or produced within the body, creatine is then transported into muscle cells where it is transformed into phosphocreatine.

What is creatine used for?

Its main role is in energy production, especially for short and intense efforts, such as weight lifting. Every time our cells expend energy, they are consuming ATP (adenosine triphosphate) which is the energy “currency” in our metabolism. When ATP is consumed to generate energy it loses a phosphate group, so from adenosine triphosphate it becomes ADP: adenosine diphosphate. Creatine replenishes ATP reserves starting from ADP. In fact, creatine combines with a phosphate group to form phosphocreatine, and subsequently by transferring its phosphate group to ADP it replenishes the ATP reserves and returns to being creatine. This reserve is very useful for short, intense and repeated efforts (typical of bodybuilding and gym).

In fact, one of the first studies observed that after 4 weeks of supplementation with creatine monohydrate, professional weightlifters were able to significantly increase the number of bench press repetitions compared to the control group (Earnest et al., The effect of creatine monohydrate ingestion on anaerobic power indices, muscular strength and body composition, 1995).

Furthermore, there are studies that show that even those who do endurance sports can benefit from creatine supplementation. In fact, creatine can help endurance athletes in improving rapid recovery, increasing anaerobic capacity and muscular endurance, and building strength (Claudino et al., Creatine monohydrate supplementation on lower-limb muscle power in Brazilian elite soccer players, 2014 ). This metabolite also helps reduce muscle damage and can increase glycogen storage in muscles if taken after training (van Loon et al., Creatine supplementation increases glycogen storage but not GLUT-4 expression in human skeletal muscle, 2004).

Above all, creatine is appreciated because it contributes to the increase in lean mass, in fact the intake of creatine is known for its role in increasing muscle mass. Scientific studies have shown that creatine supplementation can improve strength and muscle mass, especially when combined with exercise (Olsen et al., Creatine supplementation increases the increase in satellite cell and myonuclei number in human skeletal muscle induced by strength training, 2006).

What does creatine monohydrate mean?

The term “monohydrate” refers to the presence of a water molecule bound to each creatine molecule. This form is very popular in sports nutrition supplements, as it has been extensively studied and proven effective in improving muscle strength, energy and athletic performance, as well as promoting muscle growth. Its popularity also derives from its good solubility in water and its general stability.

What is Creapure® creatine?

Creapure® is simply a registered brand of creatine monohydrate that is renowned for its high purity. This creatine is produced in Germany with a manufacturing process that ensures a high level of purity and quality. This manufacturing process significantly reduces impurities such as creatinine, diyanamides, and dihydrotriazines, which may be present in slightly higher levels in lower-quality forms of creatine. CREATINA+ EXTRAGOLD contains exclusively Creapure® creatine.

Is creatine bad for you?

Many wonder what the negative effects of creatine are, and some wonder: does creatine cause hair loss?

Most of the speculation regarding the relationship between creatine intake and hair loss stems from a single study conducted on 20-24 year old male rugby players. This study found increased dihydrotestosterone (DHT) concentrations in the blood following creatine intake (25 g/day for 7 days, followed by 5 g/day for another 14 days). Although variations in these hormones, particularly DHT, have been associated with some cases of hair loss, the current body of scientific evidence does not indicate that creatine intake increases total testosterone, free testosterone, DHT, or cause hair loss or baldness (Antonio et al., Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation, 2021).

Creatine is the most studied supplement ever and with a huge number of bibliographical references. The international society of sport nutrition (ISSN) (Kreider et al., International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand, 2017) establishes that there is no scientific evidence that its intake leads to long or short term negative effects. Furthermore, ISSN describes it as the most effective supplement for sports performance.

How and when to take creatine?

Taking creatine offers some flexibility, allowing athletes to integrate it into their diet in various ways. A fundamental aspect to consider is its thermal stability, which makes it possible to mix it with any drink, without worrying about loss of effectiveness. This feature makes it convenient to take in different contexts, both before training and at any time of the day.

An effective method to optimize the absorption of creatine is to take it in conjunction with a meal rich in carbohydrates. Carbohydrates increase insulin levels in the body, making it easier to transport creatine into the muscles. For those who are concerned about water retention (a common but generally mild side effect of creatine supplementation) a useful strategy may be to divide the daily dose into two parts to be taken before training and immediately after exercise. In fact, pre-workout creatine is spent for energy and performance purposes, while post-workout creatine is very important for recovery, in particular by promoting the replenishment of muscle glycogen reserves (van Loon et al., 2004). Furthermore, this division can help reduce potential problems related to water retention, while maximizing the effectiveness of creatine in supporting performance and muscle recovery.

Creatine doses

To maximize the benefits of creatine, it is essential to gradually increase its concentration in the muscles. There are two main approaches: the first is the loading phase, which involves taking around 20 grams of creatine per day for a week.

This method speeds up the muscle saturation process, but is not the most efficient. In fact, taking too much creatine in a short time can strain the intestines and result in a waste of product and money, as the body is unable to absorb so much creatine in such a short time.

Therefore, we recommend a more gradual and sustainable approach: the intake of 3-6 grams of creatine per day, depending on body weight, maintained constantly for at least a month. This method ensures optimal muscle saturation, minimizing side effects and maximizing the efficiency of supplementation.

Hidden benefits of creatine: the benefits for the brain

In addition to its well-known benefits on physical performance, creatine is also emerging as a potential ally for cognitive health. Recent studies suggest that this supplement can improve certain cognitive functions, especially in contexts of fatigue or lack of sleep. Furthermore, creatine shows promising neuroprotective properties.

These aspects open new perspectives on the use of creatine, extending its applicability well beyond the sporting context, towards a broader field that includes mental and neurological well-being (Dolan et al., Beyond muscle, 2019). However, it is important to note that more research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms and potential benefits of creatine supplementation for the brain.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Antonio, Jose; Candow, Darren G.; Forbes, Scott C.; Gualano, Bruno; Jagim, Andrew R.; Kreider, Richard B.; Rawson, Eric S.; Smith-Ryan, Abbie E.; VanDusseldorp, Trisha A.; Willoughby, Darryn S.; Ziegenfuss, Tim N. [Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation; 2021]: Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show?, in: Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 13.

Claudino, João G.; Mezêncio, Bruno; Amaral, Sérgio; Zanetti, Vinícius; Benatti, Fabiana; Roschel, Hamilton; Gualano, Bruno; Amadio, Alberto C.; Serrão, Julio C. [Creatine monohydrate supplementation on lower-limb muscle power in Brazilian elite soccer players; 2014]: Creatine monohydrate supplementation on lower-limb muscle power in Brazilian elite soccer players, in: Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, vol. 11, p. 32.

Dolan, Eimear; Gualano, Bruno; Rawson, Eric S. [Beyond muscle; 2019]: Beyond muscle: the effects of creatine supplementation on brain creatine, cognitive processing, and traumatic brain injury, in: European Journal of Sport Science, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–14.

Earnest, C.P.; Snell, P.G.; Rodriguez, R.; Almada, A.L.; Mitchell, T.L. [The effect of creatine monohydrate ingestion on anaerobic power indices, muscular strength and body composition; 1995]: The effect of creatine monohydrate ingestion on anaerobic power indices, muscular strength and body composition, in: Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, vol. 153, no. 2, pp. 207–209.

Kreider, Richard B.; Kalman, Douglas S.; Antonio, Jose; Ziegenfuss, Tim N.; Wildman, Robert; Collins, Rick; Candow, Darren G.; Kleiner, Susan M.; Almada, Anthony L.; Lopez, Hector L. [International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand; 2017]: International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine, in: Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 18.

van Loon, Luc J.C.; Murphy, Robyn; Oosterlaar, Audrey M.; Cameron-Smith, David; Hargreaves, Mark; Wagenmakers, Anton J.M.; Snow, Rodney [Creatine supplementation increases glycogen storage but not GLUT-4 expression in human skeletal muscle; 2004]: Creatine supplementation increases glycogen storage but not GLUT-4 expression in human skeletal muscle, in: Clinical Science (London, England: 1979), vol. 106, no. 1, pp. 99–106.

Olsen, Steen; Aagaard, Per; Kadi, Fawzi; Tufekovic, Goran; Verney, Julien; Olesen, Jens L.; Suetta, Charlotte; Kjær, Michael [Creatine supplementation augments the increase in satellite cell and myonuclei number in human skeletal muscle induced by strength training; 2006]: Creatine supplementation augments the increase in satellite cell and myonuclei number in human skeletal muscle induced by strength training, in: The Journal of Physiology, vol. 573, no. Pt 2, pp. 525–534.

+Watt Advice

Recommended use: we recommend taking about 3 g of creatine in total before and after training for about a month.